Baker Lake is something of a Nunavut anomaly. It’s the territory’s only community not on the coast, it’s near the geographic centre of Canada, and its main employer isn’t government.

Situated about 300 kilometres inland from the coast of Hudson Bay and accessible by water via Chesterfield Inlet, the hamlet is spread along the edge of its namesake lake, with tiered streets leading up from the shoreline. There’s a distinct lack of trash along the streets, and the town is easy to navigate. It’s quiet and friendly. Despite a full-scale gold mine operating outside of the hamlet, you’d be hard pressed to find any evidence of it if you're standing in the centre of town.

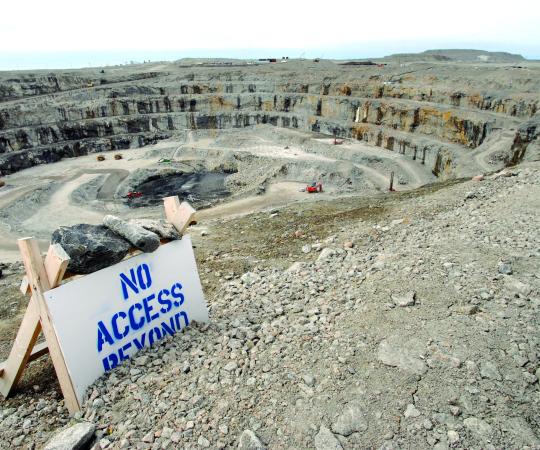

A large bypass road loops around north of town, with access to the dump, sewage disposal, fuel depot, barge dock and the 110-kilometre road to the Meadowbank mine.

Ken Hachey, a hamlet councillor and owner of Arctic Fuel in Baker Lake, says when Agnico Eagle arrived in 2009 to begin construction of the mine, the hamlet was careful to avoid the industrial look of a mining town. “We wanted to keep the traffic from coming into town,” Hachey says. “Four or five years ago, you always saw Agnico Eagle pickup trucks driving through town. Now you maybe see one a day. Maybe.”

But it was hard not to notice when the Quebec-based company first came in, Hachey says. Eager to get the construction phase over with as quickly as possible, they hired outside contractors to get the work done. “It was just too big for all of us to comprehend what was going to happen here, during the construction phase,” Hachey says, “We all just held on for the ride for a few years until we got our feet on the ground and started assessing what the heck just happened. It was a real learning experience.”

Then when the mine started, they hired up all the experienced workers in town. This left local employers like Hachey scrambling. Now there are a good 170 Baker Lake residents working at the mine, and many others working for companies such as Arctic Fuels that directly benefit from the mine.

For Peter Tapatai, a local businessman and lifelong Baker Lake resident, it’s difficult to describe how beneficial the mine has been to his hometown—he knows the subject of mines in Nunavut is controversial. “The employment that is coming in from Meadowbank has created in my view—how do I say it?—fathers and mothers are taking a role to show their children that you can work. And it’s building really strong self-esteem.”

Baker Lake has essentially transformed from a town dependent on welfare to one running on a wage economy. In 2005, 740 residents of the hamlet were on social assistance. In 2013, after the mine had been running three years, that number dropped to 523—almost half the rate of unemployment for the rest of Nunavut and one of the lowest of all communities in the territory. The hamlet also had one of the lowest median incomes in the territory before Meadowbank; now it’s closer to the territorial average. (Regional centres such as Cambridge Bay, Rankin Inlet and Iqaluit skew the numbers because of the large amount of middle and higher tier government jobs located there.)

The town’s population has also risen by about 20 percent since 2006 and now sits at about 2,164. Of that, Baker Lake’s non-Inuit population has nearly doubled in the same time, from 152 to 295.

But the higher wages and population seem to have brought the same ills they bring other booming resource towns. Criminal violations in the hamlet have more than doubled since 2006, and the violent crime rate is higher than the average Nunavut community, though it was less than half of what it is now versus 2009, before the mine arrived.

Tapatai says the positives outweigh the negatives. He sees Inuit using the two-weeks-on/two-weeks-off schedule to hunt and spend time with family, while also advancing their careers. “You know what really hurts me is [the idea] that Inuit and the aboriginal community are only good to do labour work … We’re going to be living here all our lives. If an Inuk is only going to be a labourer and not move forward, there’s something wrong with that,” Tapatai says. “Agnico Eagle has told us they would really like to see an Inuk being able to take a position somewhere higher. Not many people talk like that.”

But the Meadowbank mine is only expected to be in production until 2018. Although that’s about a year longer than originally planned, the end is not that far away. Many Baker Lake families are entrenched in the wage economy, and trained for mining jobs. “After the mine closes, we’re going back to the way it was in the early 2000s,” Hachey says. “It’s not going to be good, let’s put it that way. You’re going to have, easily, 300 people looking for jobs in the community overnight.”

Agnico Eagle is already looking at opening a satellite operation—Amaruq—about 50 kilometres northwest of the Meadowbank mine, to keep producing gold in the region (see pg. 57). Now that Baker Lake has experienced its first mining boom, skilled and experienced local workers and service industry employers should be better positioned to take advantage of that project.

In the meantime, the community is struggling with another exploration project—a uranium mine being proposed by French company Areva. It’s controversial, and has received so much criticism locally that many refuse to speak on record about it. In late September, the Kivalliq Wildlife Board wrote an open letter to federal candidates in Nunavut asking them to declare their position on the protection of caribou calving grounds. And there’s still some opposition to the current Meadowbank project from many Inuit in the area. There have been concerns about the impact of the mining road to Meadowbank—at 110 kilometres, it’s the longest in Nunavut—on caribou.

But Tapatai, a hunter himself, thinks some of those worries are overblown. “I think once the caribou want to cross the road, they cross the road.”