THE KINNGAIT STUDIOS PRINT SHOP at the West Baffin Cooperative issued its first series in 1959, introducing artists who’d go on to achieve international recognition in the years that followed. Their work brought Inuit life, culture and perspectives to global audiences. But the world saw only a small fraction of the drawings Kinngait’s artists created—and the selected works stuck to a few familiar themes. Art fans and collectors outside the Arctic were drawn to images of wildlife, hunters and spirits, so the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council—a federal agency that chose the pieces to be released each year from 1961 to 1989—focused on those themes. Images that opened a larger window on Inuit life, its joys and hardships, remained unseen in workshops scattered around the Arctic.

Fortunately, Kinngait preserved the work, creating an archive of 90,000 drawings from the studio’s first three decades. Taken together, the images create a fuller, more nuanced picture of Inuit life in the era before audiences became more open to the bigger picture. The McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, which has held the archive in trust since 1990, has launched a searchable online archive of the drawings called Iningat Ilagiit, meaning “a family place.” It is, frankly, a treasure. The gallery also presented a show curated by Emily Laurent Henderson that closed in August and published a companion book called Worlds on Paper. Consider this a recommendation. And if you can’t wait for your order to arrive, we present a sampler in the pages that follow.

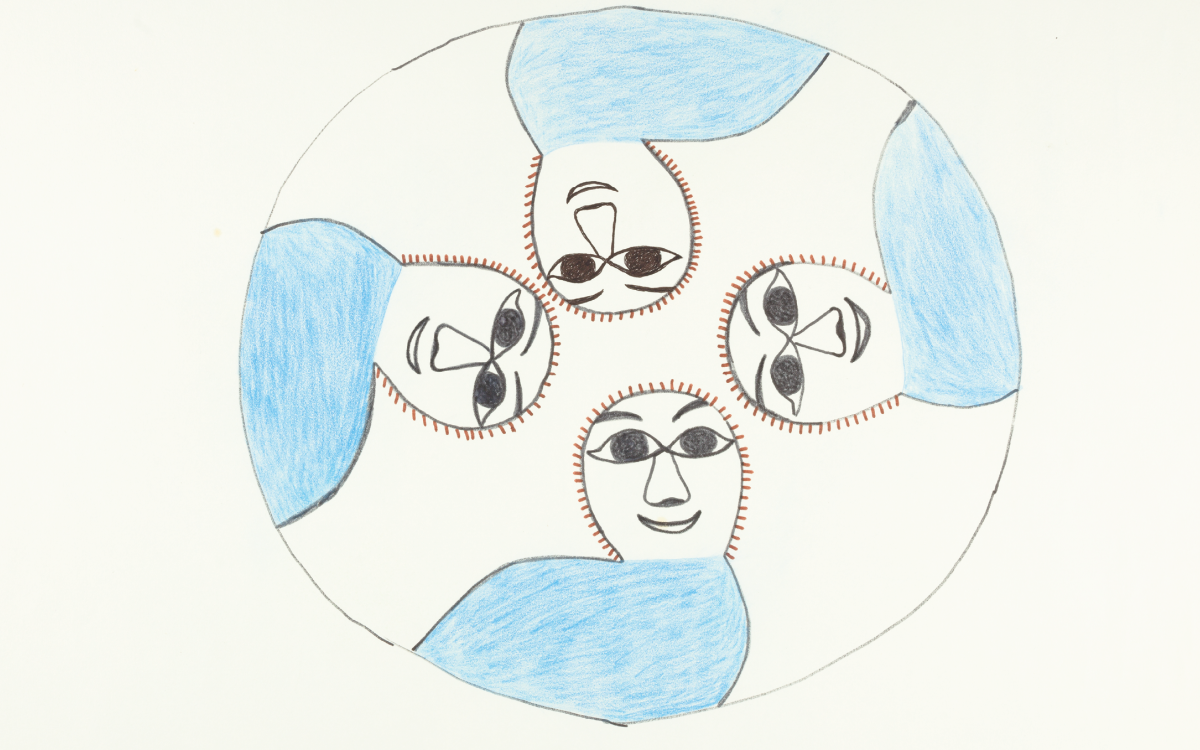

Tattooing

Tattooing began to fade in Inuit culture with the growing influence of Christianity in the 20th century. The church viewed the tradition as primitive and ungodly, and it sought to stamp it out, along with other cultural practices. Although tattooing has enjoyed a revival in the 21st century, it is not well represented in the art promoted during the first decades of the Inuit art phenomenon. But the Kinngait archive shows it remained important to how Inuit saw themselves and their heritage, as this drawing by Peter Pitseolak from the 1960-66 era suggests.

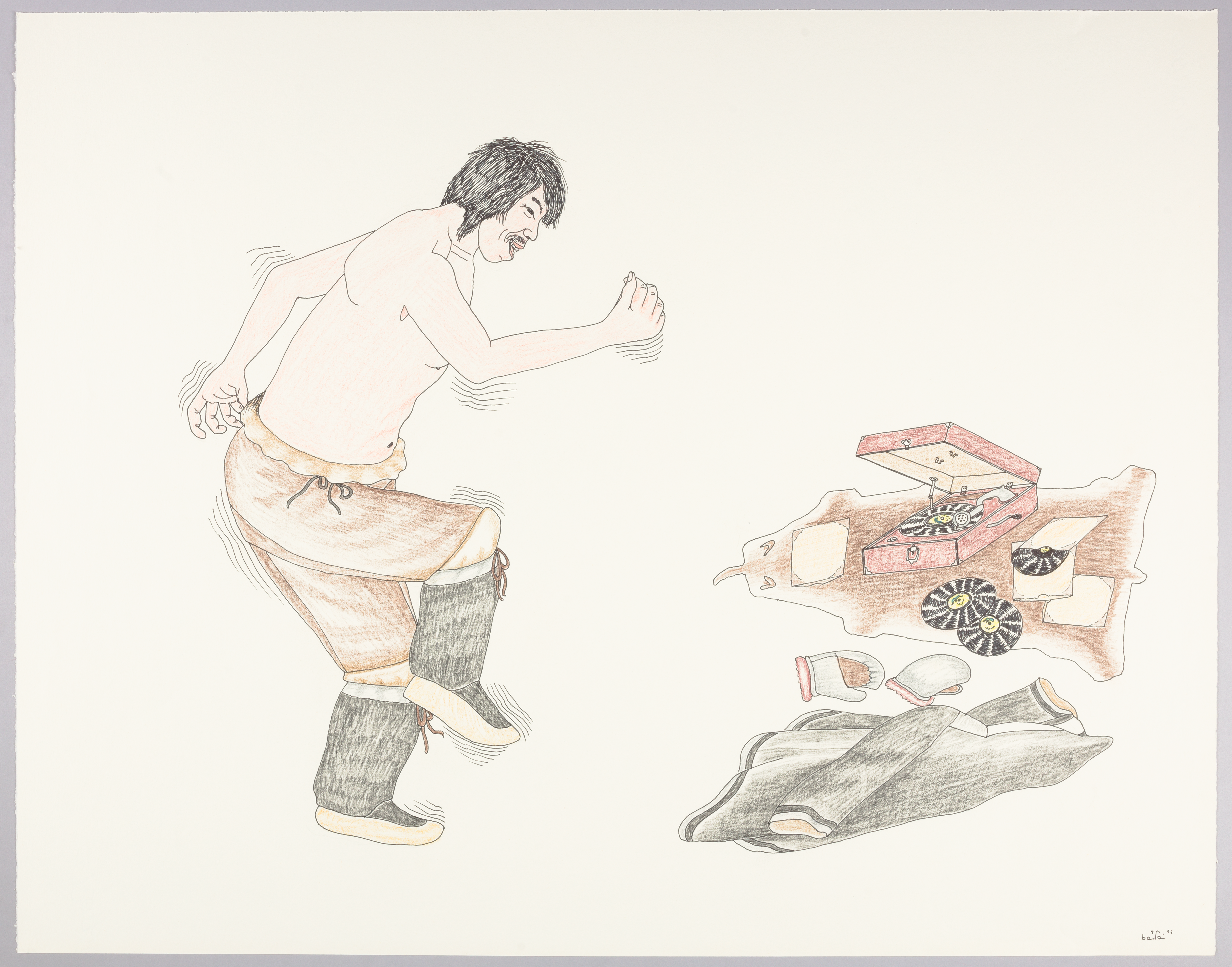

The Lighter Side

In this pair of drawings from 1984-85, Kananginak Pootoogook offers a fun glimpse of life beyond the standard themes in Inuit art that reached large audiences. A skilled hunter comes to a trader with a bundle of fox furs. The trader assumes the man is looking for modern tools, specifically a rifle and bullets. But the hunter does perfectly well with his bow and harpoon. What he doesn’t have is a record player and a few albums.

Moments of Hardship

The growing influence of western society in the Arctic forever altered Inuit life. Positives include the creation of art studios and the introduction of useful tools, such as snow machines. But the negatives are myriad. Napachie Pootoogook offers a glimpse of one in this drawing from 1981. When an RCMP officer arrives at a camp, one child flees as another runs into the arms of a parent and still more hide in a tent. It’s reasonable to guess the officer is there to take the children away to a residential school.

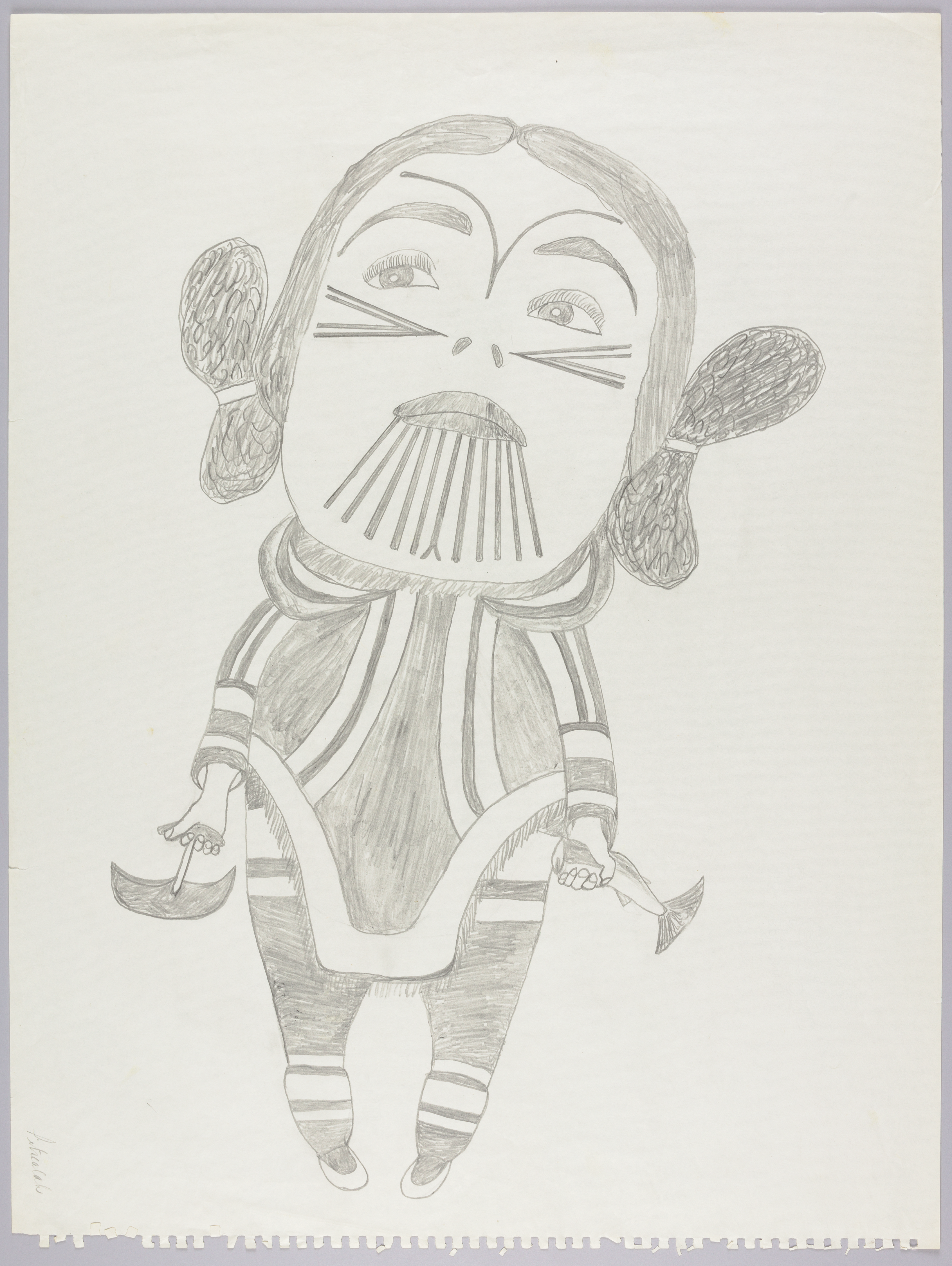

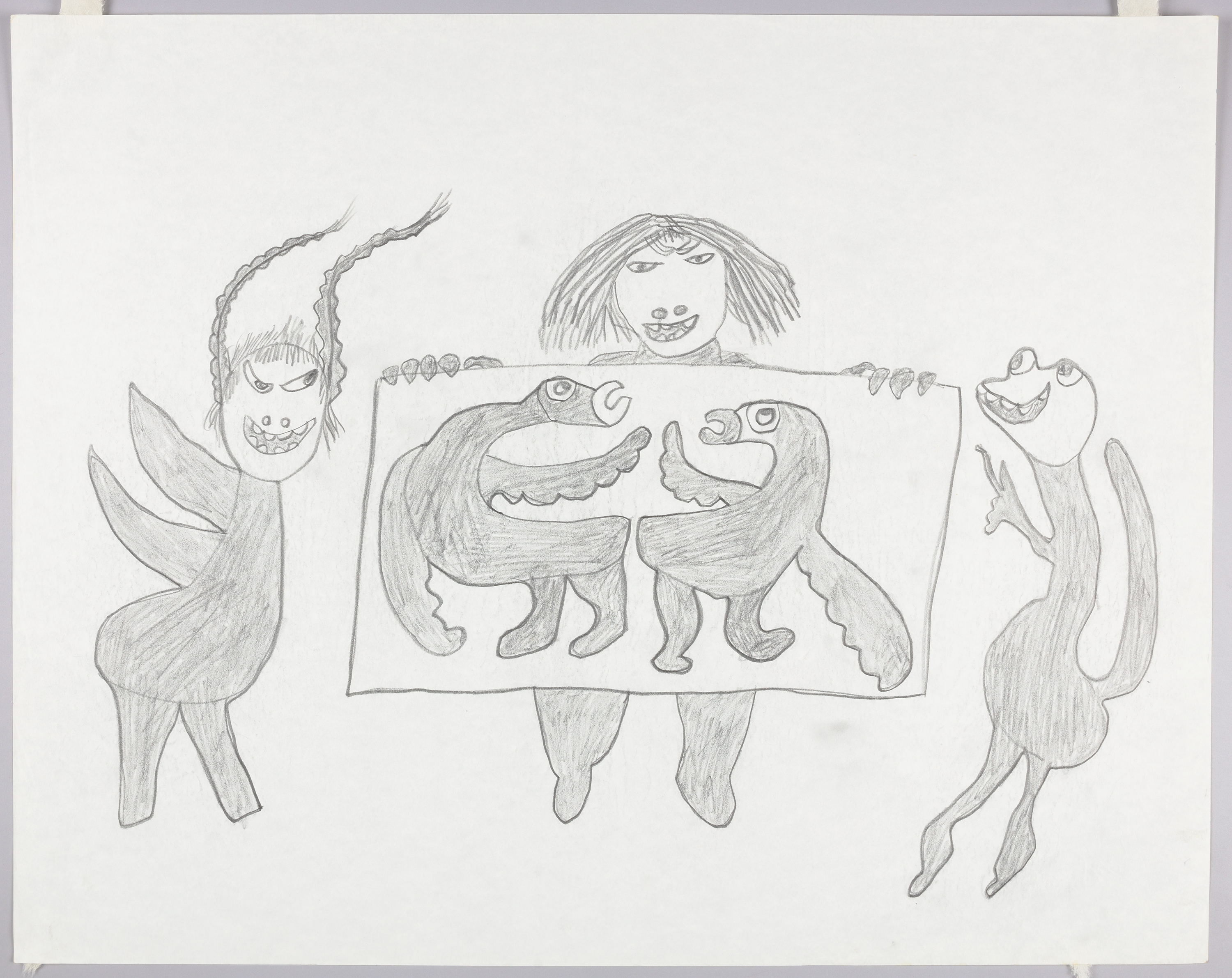

Art About Making Art

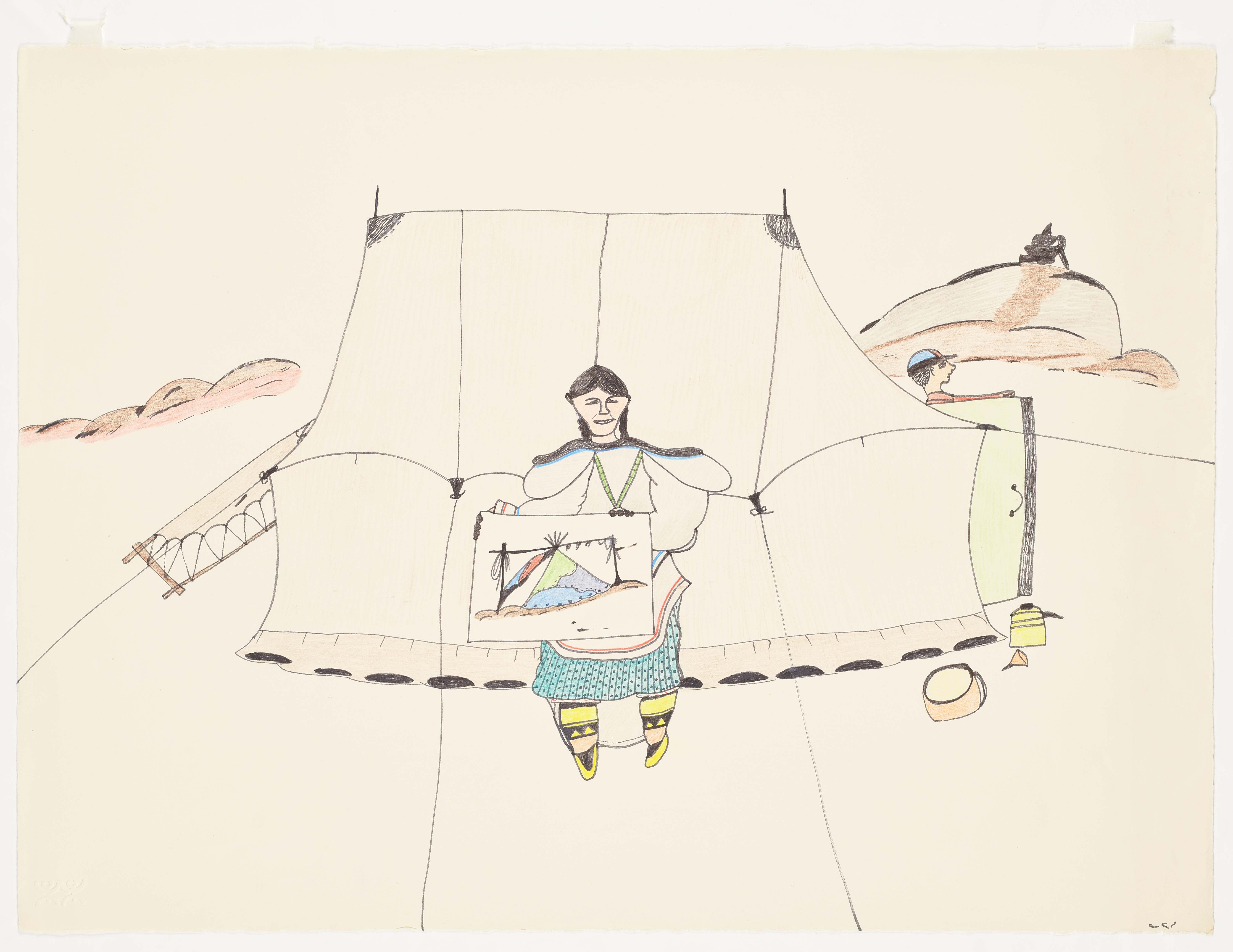

A theme that shows up early in the archive is artists doing their work, which was becoming an important part of life for Inuit and Inuit families. The first drawing here (top left) is by Pitseolak Ashoona, a self-portrait from around 1962 in which she shows a new work. The second (above), called “Drawing of My Tent,” was made in 1981 by Napachie Pootoogook, Pitseolak’s daughter.

The third, “Showing a Drawing” (top right), from 2001-02, is by Annie Pootoogook, daughter of Napachie and granddaughter of Pitseolak. The work is not part of the Kinngait archive (it appears here courtesy of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia), but it shows creativity moving through generations. Annie Pootoogook’s life ended early and tragically in 2016, but her influence continues. In April, ARTnews named her piece “Man Abusing His Partner” one of the best artworks of the 21st century.