“The whole town of Yellowknife is roaring drunk.”

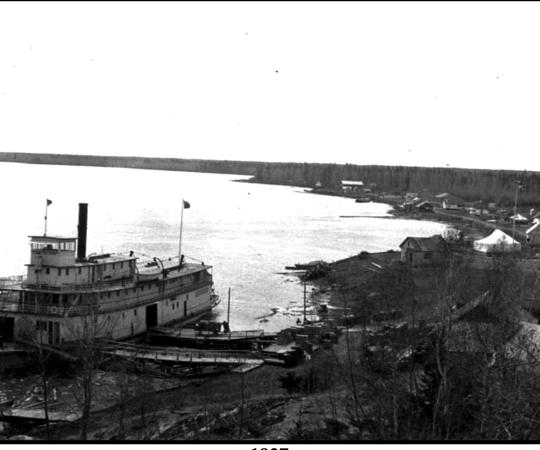

Jill Kidder was among a handful of women living in Yellowknife when she wrote those words to her family in 1947, at a time when most of the town’s residents were miners and nomads, living within a cluster of shacks and tents along unpaved roads.

“The streets are full of weird, old men reeling about in their undershirts, and the lake is full of wet, old men who didn’t quite make it to, or from, the liquor store, which is on an island.”

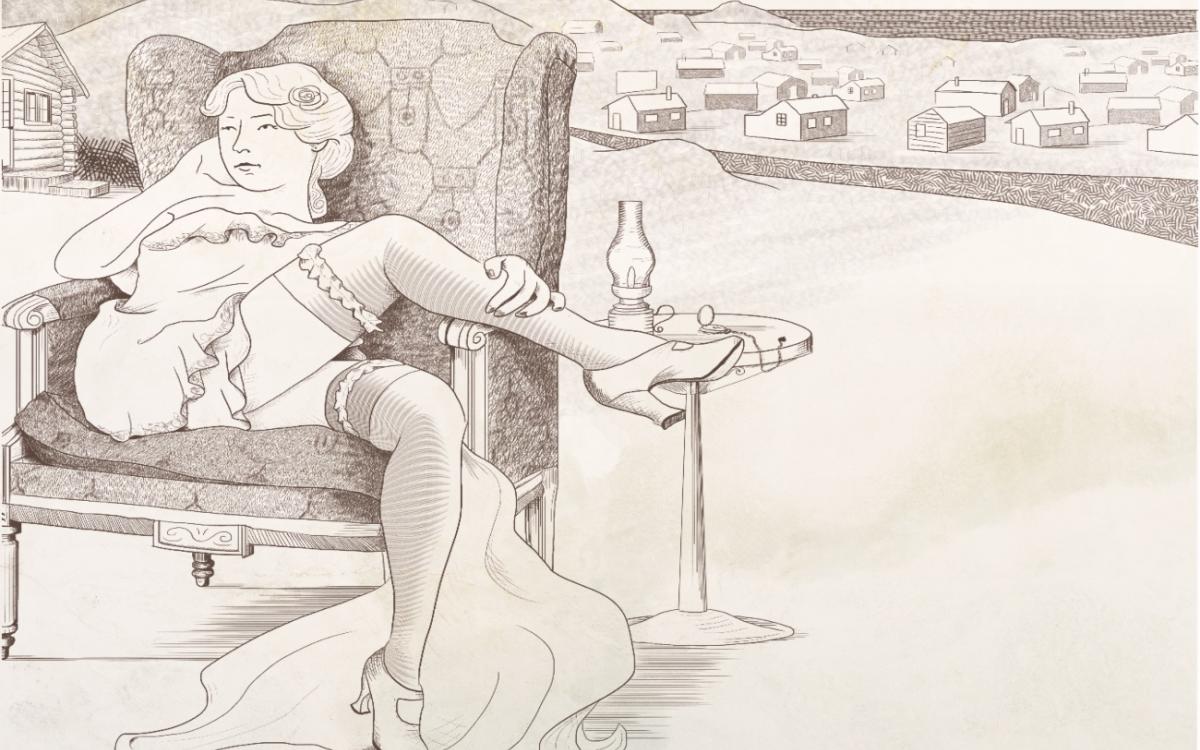

Yellowknife had only just become a settler community 13 years earlier and most had come for the mining. Naturally, in a town full of men far from the rest of Canada, there also came women who were ready to fill a specific need, for a price. As a few Yellowknife tales about this historical period say, the town was full of miners and the women who “mined the miners.” They set up tents and backrooms in what came to be known as Glamour Alley. It was scattered, seedy and, much like the town’s gold, hidden behind a gritty exterior. Nearly a century later, those women’s names remain unknown. Unlike the

romanticized tales of the Klondike Days, and the madams who thrived in the Yukon, the story of Yellowknife’s Glamour Alley is still hidden away.

Take a walk down to Old Town today and you’ll end up in a vibrant neighbourhood where art takes over every corner—from wooden pallets hanging along fences to the colourful houseboats scattered across the bay. There’s even a painted dumpster, featuring a bear and some nude swimmers. But back in 1940, it was far more of a ramshackle affair.

When Con Mine opened, settlers moved into shacks, tents, and log cabins clustering in what was then the town centre. The community had few businesses at the time—a couple of hotels, a café and a one-room school. With about 1,000 residents back then, Yellowknife was a typical frontier town, which would have hardly been complete without its own red-light district. Although it was home at one point to 14 sex workers, Glamour Alley was far more inconspicuous than counterparts in other far-flung mining towns. Located in Willow Flats (which leads into Old Town), it was near the town’s centre and just down the road from the schoolhouse. The proximity caused more than a few drunken men to occasionally wander into the school’s yard, lost in their confusion and loneliness.

Prostitution was “being done in the shadows of legitimate businesses,” says Yellowknife historian Ryan Silke, and in historical records, none of these people have names. “If there’s any mention [in the archives], they’re given generic names like Blondie and Red. There were ones who were named Drill Bit and Core Barrell.”

It’s assumed the sex workers headed north to follow the miners, but there’s no indication of where exactly they came from or if any were local Indigenous women. The lack of answers is partially due to the transient nature of the town. “Ninety-five per cent of people didn’t leave a record of any kind, except maybe employment at the mines,” says Silke.

There are no books nor reports dedicated to sex work within Yellowknife. It seems past historians were uninterested in documenting these tales, as what does exist is brought up as the odd anecdote or through yarns, told in passing.

One of those excerpts comes from the autobiography, Miners and Moonshiners, by Fred Peet. The story follows a group of women who moved in close to Con Mine in 1937, a year after it first opened.

At that time, Con Mine had ditched its original living quarters of tents to move its workforce into permanent camp buildings with bunk houses and an 18-bed hospital. But the vacated real estate wasn't empty for long.

“Their old tent camp was abandoned, so that’s where the prostitutes moved in,” says Silke. “There was a lot of activity going on and the mine management didn’t look too favourably on having ladies move in right next door to the camp. Essentially they were squatting.”

Seeing sex work as a distraction to its labour force, management didn’t want the women in the community, let alone so close to the campsite. So, they sent someone to go over and tell the women to leave, which no one was keen on doing. As a story in the book goes, one of those who got the boot had a temper and

had, on another occasion, trashed the Wildcat Café for apparently little reason.

When the women were told to leave, it’s assumed some of them returned to other tents and shacks around Glamour Alley. Others may have left town altogether. Based on the written documents of the time, it seems no one kept track of them.

As is the case in most of history, these stories were told mostly by men, for men. The voices of women and marginalized people aren’t often included. And that, says University of British Columbia professor Mona Gleason, can obscure our view.

“It’s got a lot to do with women’s history, but also the silencing of those who were not seen as important to historical records—from a western point of view,” says Gleason. “It’s not that those women didn’t exist or that their work wasn’t meaningful or that their history wasn’t important. It’s just that they’re caught in a power dynamic that has literally disempowered them.”

The stories told can be sometimes crass, or will relay tales about men doing what they can to get what they want from women. Take, for example, the story of yet another early Yellowknifer, nicknamed Blondie, who was potentially both a sex worker and bootlegger.

“Her occupation is unclear,” says Silke. “All we know is that she liked to party and was a source of bootlegged liquor.”

The story goes that Blondie had some of the town’s best whiskey on hand. And so one night, a group of men knocked on her door in search of a drink.

“Blondie wasn’t too willing to part with her bottle of whiskey and she didn’t want to party, so she said to go away, come back another time,” Silke says. “The men then went to get a bulldozer and slung a chain around her shack and started dragging the shack to the middle of the [frozen] lake and said, ‘We’ll move you back if you give us your bottle of booze.’”

The story ends with Blondie reluctantly surrendering her whiskey and the men returning her cabin to land, drink in hand.

Bootlegging was a common practice among men and women in those early days. Although drinking was considered a vice, it was still legal. Yellowknife’s first liquor store opened in 1939, and a beer parlour opened in 1940. However, Silke describes the government’s attitude toward drinking as “paternalistic.” It wanted to keep liquor out of the hands of miners and Indigenous people. Therefore, drinking in public as well as in the mining bunks was prohibited. Much like the rest of Canada during the early 1900s, alcohol was meant for medicinal purposes. Residents had to apply for a permit through the RCMP, which Silke says cost about two dollars a year (about $35 in 2021). Each permit was limited to a specific amount of booze—usually spirits, as beer was more expensive—and it had to be picked up through the RCMP.

“Any evidence of you turning around and selling it, then you’re bootlegging,” explains Silke. “The cops’ job was to try and stop that from happening, but they didn’t have a lot of success doing that.”

One of those illegal businesses was run by Agathe Lessard, grandmother of Yellowknife musician Norman Glowach, who recounts the story of his “Bootlegging Granny” in his stage show. Back in the 1940s, Lessard had moved up north with her husband, Louis Lessard, and their six children. But life in Yellowknife was not easy and the couple made little money from their Latham Island business, Rex Café.

“It was a small little log cabin and people would come in and run up tabs and wouldn’t pay, they wouldn’t have enough money, or they would leave town,” explains Glowach in an interview.

So, his grandmother started selling liquor at the back of the café to support her children and make ends meet. Glowach stresses that Lessard knew about the negative effects of alcohol, but there were few other jobs in town.

“Basically, there was just mining and a lot of drinking,” Glowach says. “The fact of the matter is, if she didn’t have to do it, she wouldn’t have done it.”

The story of “Bootlegging Granny” is only known as it’s been passed on down through Lessard’s descendants. But when it comes to a few male bootleggers, their stories are public record and well-documented. Take Vic Ingraham and Pete Raccine—who Ingraham Trail and Raccine Drive are named after. The two were owners of some of the city’s first hotels (the Corona Inn and Yellowknife Rooms). And they were also bootleggers. While Ingraham was apparently more careful about getting caught, it’s known that Raccine was busted for selling alcohol without a permit in 1940. But penalties were not stiff. They usually resulted in a modest fine or a permit ban for one year. After that, Raccine was free to buy alcohol again, which he did without hesitation.

Today, Ingraham and Raccine are some of the most well-known names in Yellowknife. Those who sold alcohol are often memorialized, while those who sold sex are forgotten. At least, in some places.

Unlike Yellowknife's Glamour Alley, Dawson City's Paradise Alley has been glamourized over the years. So much so, that Alex Somerville, Dawson City Museum’s executive director, refers to that bygone era of gold miners, saloons, and brothels as the “Klondike Imaginary.”

“There are thousands of people around the planet who have a mental image of the Klondike, despite never having been here or really seen photos of Dawson City.”

And he’s right. Most people can imagine the dusty roads lined with wooden bars and storefronts connected in a row. The city’s architecture doesn’t look too different today, only the colourful buildings stand over parked cars, and there are certainly no women in corsets and chokers sitting outside brothels, inviting johns inside. Instead, tourism operators invite people into the very same buildings—only they’re now museums.

Like in Yellowknife, the names of the Yukon’s prostitutes are not well-documented, but the madams who ran the brothels are celebrated, even today. “Madam Ruby Scott is her name and is an indelible part of history,” says Somerville, naming some of the famous women of the 1920s. “Her former brothel is a national historic site… Likewise with Bombay Peggy Dorval. Her former brothel transformed into a boutique hotel and cocktail bar and has a reputation as a building that used to be a brothel.”

Dawson City’s brothels went up in the southern part of the city after World War 1, in what was known then as Klondike City. Prior to that, most women worked independently in cabins or in their homes—often with a card in their window stating they were in good health. The territorial government required sex workers to get checked monthly for venereal disease.

The local government’s view at the time was fairly liberal compared to other cities’ approach to sex work. Sommerville says the Yukon realized there wasn't any hope of eliminating the trade. “If prostitutes were forced out of business… you would just be forcing out the ones you can see and know about,” he explains. “But as long as it was visible, it could be monitored… I’m not an expert on sex work in Canada, but I have learned that that position by the Yukon administration and law enforcement was shocking in Ottawa.”

Yellowknife’s first practicing lawyer, C.A. “Chuck” Perkins, may have been taking a page from the Yukon’s books in the 1940s when he suggested legalizing prostitution in the Northwest Territories—for the sake of both the johns and sex workers. Perkins described prostitution as a “necessary evil,” since there were few women in town at the time, excluding the miners’ wives.

“All these miners, bushmen, and prospectors were looking to unwind and there was that mentality that prostitutes were important for the mental health of the community,” explains Silke.

Perkins argued that by legalizing it, sex workers could be safe from venereal diseases and protect not only themselves, but the people who paid for their services. Unsurprisingly, this idea was immediately shot down in Ottawa. Sex workers continued to operate in the shadows.

Had Yellowknife—and the rest of Canada—looked at sex work through the Yukon’s lens, history may have turned out differently, says Gleason.

“In the past, had we been more realistic and open about sex and sexuality, all that stuff would have been much safer for women. There wouldn’t have been the horrible kind of health scares, and also the reality of being a sex worker in the ’30s and ’40s was really dangerous,” she says. “It was just rich with exploitation.”

These days, views on sex work are becoming more progressive in Canada and historians are helping to give marginalized people a voice in historical records. “One of the things that comes up for historians now is, how can we change people’s minds about what is considered historically significant?” Gleason adds. “The goal of history is to talk about change over time and to locate stories of those who lived through those experiences. It’s not just about what the prime minister did because that leaves out way too many people.”

It’s practically impossible to know how, or even if, the women of Glamour Alley would have wanted their stories to be told. Perhaps some tried, but were criticized or went unheard. Others may have returned south and preferred no one was the wiser to their past career. The unfortunate thing is, there’s no way of knowing. But while we can’t change the past, we can change the way we see sex workers’ stories. We can look at how their role significantly changed Yellowknife history and begin to see Glamour Alley in a new light.