Not just home to ice and snow, this gigantic and often-ignored part of Canada has long been a theatre of human drama, deep and rich culture, and international politics. We’re putting faces to the names of these incredible islands.

A matter of pride

How a nagging suspicion opened the passage

When Captain John Ross said he saw mountains at the end of a strait into Lancaster Sound on his 1818 expedition to find the Northwest Passage, several officers on board doubted the veracity of his claims. Nonetheless, the ships turned back to Britain before moving any farther into the passage’s eastern gate.

It didn’t sit well with William Parry, lieutenant of the expedition, so he set out again in 1819 captaining HMS Hecla, with HMS Griper following his lead. The crew headed straight for Lancaster Sound. After a detour south into Prince Regent Inlet when ice blocked their way, they would prove Ross’s “Crocker Mountains” a fiction, sailing straight through Lancaster Sound and all the way to the south shore of Melville Island to spend a long winter locked in by ice.

The site, known as Winter Harbour, is marked with a monument in Parry’s honour: it was, after all, one of the most productive attempts at finding a Northwest Passage. (Imagine all the lives and money—and human drama—that would have been spared had ice not impeded Parry.) His name would also be given to the cottage country town of Parry Sound, Ontario and to a crater on the moon. Parry’s venture, attaining the region of the archipelago now known as the Parry Islands, opened the west for explorers to follow. – EA

A home for Northern science

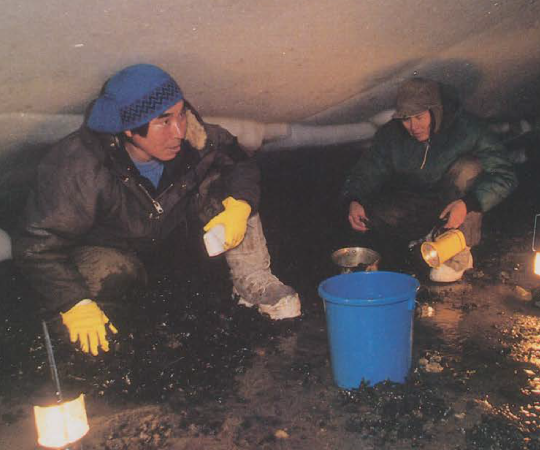

Cambridge Bay, Nunavut prepares for CHARS

One of the largest buildings in the North is under construction in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut and it’s all in the name of science. The 50,000-square-foot Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) is a major project of the Canadian government, with a pricetag of about $150 million. Once fully operational, the centre should cost about $27 million a year to run, hosting visiting scientists and researchers from across Canada and the world, as well as its 60 full-time employees.

Originally announced by the Harper government in 2012, CHARS has seen its mandate shift. Under the Conservatives, it leaned towards resource development and technology. Now, the priorities centre around studying the effects of climate change in the Arctic—and more for community interest than industry’s, according to Polar Knowledge president and CEO David Scott.

CHARS has wrapped up two field seasons and the centre is set to open this fall. – EA

Fight for the slice

Yukon and Alaska's boundary dispute

A 40-year-old dispute between the U.S. and Canada goes back to one phrase: “As far as the frozen ocean.”

An 1825 treaty between Russia and Britain—later passed on to the U.S. and Canada, respectively—set the Alaska/Yukon border at the 141st meridian. On land, it’s all good. But different interpretations of what this means beyond the shore has left a 6,250-square-mile slice of the Beaufort Sea disputed.

In Canada’s view, the marine boundary follows a continuous line drawn along the 141st meridian over the frozen ocean, leaving the waters above Yukon under Canadian rule. But the U.S. reads it as delineating a border that stops at the frozen ocean. Their position is that the standard for determining marine boundaries, an equidistance line, should be applied. That means finding the equal point between the shores on either side and then connecting the dots. This would see the border veer slightly northeast, granting the U.S. that final slice. – EA

While you're here, why not meet the East and the North?