Since 2017, I’ve been on a slow tour of the world’s hot springs. I’ve driven hours on rough logging roads in British Columbia, visited a cave spa in Colorado and soaked in the ancient Roman city of Hierapolis in modern-day Turkey. There’s something magical and mysterious about these rare places where hot water boils to the surface from deep underground.

Last spring, I kick-started the camping season with a long-weekend trip to Liard River Hot Springs in northern British Columbia, a seven-hour drive from Whitehorse. Despite its remote location, just south of the Yukon and Northwest Territories borders, Liard draws around 40,000 visitors each year. That’s a fraction of the traffic at more accessible, well-known hot springs in southern Canada, which welcome hundreds of thousands of people annually. As enchanting as these places are, they’re also fragile.

We’re not always respectful guests. The Keyhole Hot Springs, north of Whistler, were permanently closed during summer months after visitors’ food and garbage caused too many conflicts with bears. Last summer, the Xa’xtsa First Nation told Pique Newsmagazine that it collects two truckloads of rubbish from Sloquet Hot Springs, in the Fraser Valley, every week.

Perhaps at one point—when fewer people visited and even fewer shared secrets on social media—rustic, little-maintained spots functioned well. But how do you strike a balance between providing facilities and avoiding the swimming-pool-esque experience of a concrete spa like Banff Upper Hot Springs or Radium Hot Springs? At Liard, BC Parks has tried to walk the line between preserving nature and supporting tourism.

In the North, good weather on a May long weekend is never a guarantee. Sure enough, a persistent rain drizzled throughout our stay, turning campsites damp and cool. But with a few tarps and an unlimited supply of hot water, we had everything we needed. Every brisk morning and chilly evening before crawling into our sleepings bags, we walked along the two-kilometre boardwalk, above the warm-water swamp created by the springs, to the pool. There are eight in all, but only one is open for soaking. Its temperature ranges from 42°C to 52°C, which feels scalding at the source but is a pleasant soak in most of the pool.

The water’s origins are believed to be located north of the springs and over three kilometres below the earth’s surface. The heated mineral water supports unique plants and wildlife, including a specially adapted small fish called a lake chub and several orchid species. An endangered freshwater snail called the Hotwater Physa (Physella wrighti) also calls the Liard River Hot Springs home. There are only 10,000 of these snails in the world, and all live here, on the margins of two pools and an outlet stream. In total, 14 different thermally influenced species survive at Liard due to the warm water.

While the American army first built the boardwalk and pool facilities in 1942 and the park was officially designated in 1957, this place has been known for far longer. The Kaska Dena call it Tū Tīkōn—“hot water”—and consider it an important place for hunting and medicinal plants. BC Parks is working with the Kaska Dena and Fort Nelson First Nation on creating new signage to welcome visitors and explain why this place is important and how best to protect it.

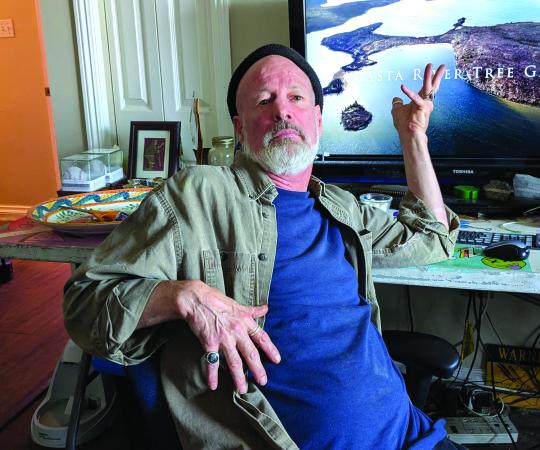

The parks agency has made thoughtful choices. “A lot of people might think, ‘Oh, the boardwalk is here, so it’s nice for me to walk on,’” says Ed Hoffman, regional director in the Omineca Peace Region, “but also it’s so you’re on the boardwalk and out of those wet areas and keeps the traffic confined.”

The rustic western-red-cedar deck and change rooms blend in with the environment, wrapping around one side of the large hot pool while leaving the other half natural. Change-room doors include small “bear peepholes,” so visitors can check for wildlife before stepping outside. The dense vegetation makes this rare area as enticing to bears as it is to people, so BC Parks erected a 2.5-metre-tall electric fence around the campground in 2020. The move was controversial, but bear management is a concern for the park, especially after a fatal bear attack in the 1990s.

On the drive from Whitehorse to Liard River, we experienced the wonder and anxiety of seeing no fewer than 34 bears on the road. I slept easy behind the fence, and it gave our group some comfort as we feasted on campfire nachos, freshly caught grayling and shredded braised beef.

BC Parks has also kept the Hotwater Physa in mind. The tiny physa are vulnerable to changes in water flow, trampling, introduced species and the cumulative buildup of chemicals like sunscreen and bug spray. For now, their population is stable. While a smaller, hotter pool used to be open for soaking, BC Parks permanently closed it to protect the snails. “We’re finding that balance between concrete pools of Banff or Radium or muck,” Hoffman says. “Using a gravel bottom and maintaining that so it keeps the water clean and makes it nice for users, but it also protects that habitat for snails.”

Almost every evening we spotted a pair of moose enjoying their dinner as we returned to our campsite. We savoured the weekend even more after our friends shared some big news: they’d be welcoming a baby later that year. I know we’ll have to teach him the essentials: how to leave no trace, how to respect the land. But I have a feeling he’ll be the kind of kid who will care about tiny endangered snails and spotting cinnamon black bears on the roadside.

Some places are so special they demand we defer to the wilderness and leave them untouched. Rules and restrictions feel cumbersome when what we all want is nature to ourselves. But increasing tourism and population growth mean we can’t take remoteness for granted.