Col. Harry Snyder lived by a philosophy that may seem strange in the modern world. He credited his extraordinary success in business to a belief that “big game hunting is the surest… way to gain strength for success in modern business and professional life.”

Born in 1882 in Vinton County, Ohio, and growing up surrounded by woods with plenty of small game to hunt, the young Harry Snyder came to realize that all he wanted in life was to hunt big game. But this burning desire to travel the world in pursuit of exotic quarry wasn’t going to be cheap. Thus, the boy who would become Col. Snyder also admitted to a burning desire to acquire the wealth that would allow him to get out there and shoot the big ones.

In his early life, Snyder worked as a store clerk, sewing machine salesman, labourer, cowpuncher, firewood peddler and many other jobs that gave him the skills and knowledge to venture into business. It’s unclear how or when he acquired the title of colonel, but he went on to develop and sell irrigated land, own a construction company, wildcat for oil and own a gold mine and coal mines in the Alberta foothills. In 1936, he was also appointed to the board of directors for the Eldorado uranium mine on Great Bear Lake and became one of its managers.

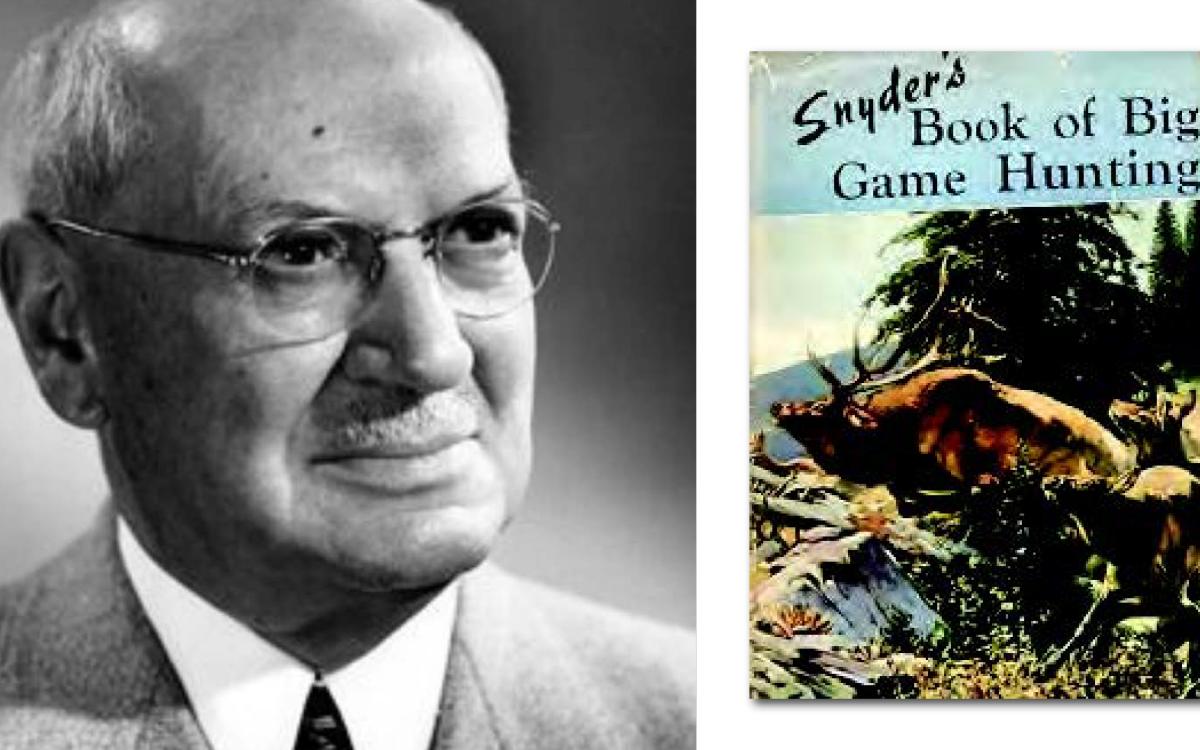

Snyder found more success than failure in his numerous business ventures, and he succeeded in his goal of spending two to three months each year hunting big game. “My jobs, good and bad, have provided the cash and time for a total of 463 weeks of hunting from 1900 to date [1950], averaging better than nine weeks per year,” he wrote in his 1950 book Snyder’s Book of Big Game Hunting.

In a June 1950 article, The New Yorker magazine called Snyder, then 68, “the dean of this continent’s big game hunters.” The story went on to quote him claiming, “I’ve shot everything there is in North America, a lot of stuff in Central and South America, practically all African and European game, and gazelles in western Africa. Lord love you, I must of shot over seven hundred head of big game. I’m not a butcher, mind you. I’ve often killed in order to eat.” In 1938, Snyder shot a world-record elephant in Kenya. It weighed an estimated eight-anda- half tons. In 1935, he shot eight wood bison in a single day and, so he claimed, shot a whale in the Inland Passage, north of Vancouver. That’s a lot of good eating.

Snyder was most interested in those animals that were not commonly hunted by other big game hunters. He hunted mountain sheep in the Nahanni, wood bison near Fort Smith, muskox along the Thelon River and caribou anywhere he could find them. These were animals that the Canadian government had designated as endangered and were under protection.

During the mid-1930s, in the middle of the Great Depression, Snyder led, and funded, three major expeditions into remote areas of the Northwest Territories. He was going to hunt what he called “forbidden game,” but not illegally. He had the blessing of the federal government, and it provided all the appropriate permits.

How did he do it? In his book, he gives advice to the young sportsman: Do what it takes to join a scientific expedition. “[M]useums send them out very often,” he claimed. “You can bet your boots that when the time comes, they’ll give you a chance to collect your game… a bison head on your wall is a marvelous trophy.”

Snyder went one step further. If there were no scientific expeditions to join, he would create his own. He would bring together government officials and directors from major Canadian and U.S. museums and offer his services as a big game hunter to obtain suitable heads and hides that could be stuffed and put on display. The icing on the cake? He offered to bring scientists and pay all costs of what would then be considered a “scientific expedition.”

For example, when he travelled into the Glacier Lake area of the Nahanni in 1934, he had permits to collect specimens of a rare species of mountain sheep for the National Museum of Canada and the American Museum of Natural History. The expedition included photographic surveyors, a geologist and a biologist, who would shed light on this unknown part of the Northwest Territories.

This was a winning situation for everyone involved. The government got its accurate maps and scientific reports, the museums got their specimens and Snyder, as he had previously arranged, got his reward and was allowed to keep some of the specimens collected.

Snyder had grand plans for many of the big game specimens he’d personally hunted. For years he had been looking for property on which he could build a home for his retirement, a place where he could display his big game trophies and his collection of paintings, books, firearms and artefacts. It would also be a place where he could sit in front of a roaring fire and entertain guests with tall stories of his hunts.

In 1942, Snyder learned that the Bar 7 Ranch in the Rocky Mountain foothills west of Sundre, Alta., was for sale. It was a huge property, about the same size as Heathrow Airport in London, and opportunity to purchase it was well timed, Snyder was 60, very wealthy and ready to settle down.

He supervised the construction of a massive log building that he dubbed “The Teepee.” A fieldstone hearth in the main hall was framed by trophy heads from around the world while the floor was covered in skin rugs. A side room, said to be 12 metres long, contained a combination of more trophy heads, rare and very valuable paintings, artefacts, books and antique rifles and pistols.

Given Snyder’s extensive travels in the Northwest Territories, “The Teepee” contained a priceless collection of Indigenous art and artefacts from the North, which is a real shame because, on the evening of Dec. 17, 1953, “The Teepee” burned to the ground. Snyder and two hired hands were “only able to save a table, a case of books and a rug.”

All that remained standing was that massive fieldstone fireplace, a fireplace that was once the focal point of Harry Snyder’s life’s work. The fireplace is now part of the big house on a dude ranch. As for Snyder, after the devastating loss in this fire he moved to Arizona where he lived out the remaining years of his life.