Colin Fraser steps out of his office and heads down to check the water intake for the desalinization plant at B2Gold’s marine port at Bathurst Inlet. This long fjord extending inland south of Victoria Island is mostly ice covered, with deceptive bits of open water, in late November. The lights from this large camp reflect brightly off the snow. In the dusk, movement overhead catches his eye—six birds, circling, flashing wingbeats in the glow of the lights.

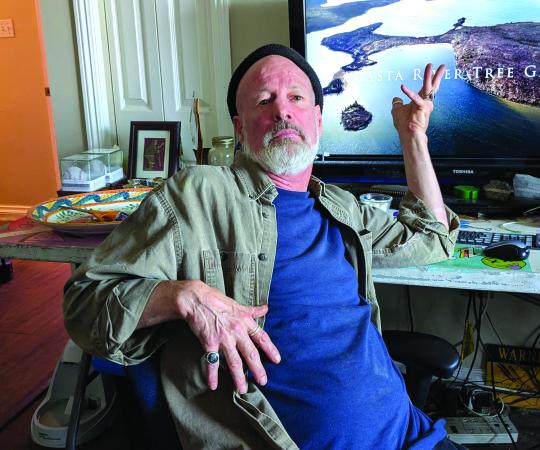

Fraser manages the 160-person operation that includes large fuel tanks, docks and an airstrip. He’s Métis and was raised in Yellowknife but spent his summers here so this area is home to him. For many years, he’s taken Bathurst Inlet Lodge guests to observe wildlife and learn about the land and the people. He knows almost all the local birds leave by late September. Few other than ravens and ptarmigan remain. So, he’s surprised by this unfamiliar sight.

The birds circle overhead then vanish. The next afternoon, Fraser is ready with binoculars and watches their narrow wings, quick wingbeats and “flap-flap-glide” flight pattern. He doesn’t know what they are.

In Yellowknife, 580 kilometres to the south, I receive a series of texts: “There’s a bunch of strange birds flying around. I don’t recognize them. Not quite the size of a gull, maybe about the size of a ptarmigan. White under wings, falcon-like wings and fat long round body.” “Maybe a bit like jaegers. Skinny wings.” “No open water round here.” He makes a sketch and takes a video with his phone.

The sketch helped a lot; the video was grainy, but I could see the birds. They had a distinctive flight pattern, typical of seabirds, maybe shearwaters. I texted Reid Hildebrandt, a local expert who runs the Yellowknife Bird Arrivals Facebook page and the Christmas Bird Count. He examined the video and agreed with my “seabirds, possible shearwaters” guess. Rare sightings require detective work and often several specialists working together to puzzle out the story. With input from Inuit across the Arctic coast, as well as people from inland areas, we confirmed it—these were short-tailed shearwaters (Ardenna tenuirostris).

Exhausted (or dead) shearwaters were being found in Aklavik, Paulatuk, Cambridge Bay, Bathurst Inlet and Gjoa Haven, all sites along the Northwest Passage. And one weary bird, far off its usual route down the Pacific, was caught by wildlife photographer Shayna Cossette at Stony Rapids, Saskatchewan. Lawrence Ruben, from Paulatuk, spotted a raven carrying a black bird and was able to find it when the raven dropped it. And in Gjoa Haven, Gibson Porter saw about 10 birds flying around. After he picked up one exhausted straggler, a wildlife officer photographed it and biologist John Chardine identified it as a short-tailed shearwater. The fate of these wanderers is depressingly clear; shearwaters cannot take off from land or ice, so no food, no water on which to rest—so they were likely doomed.

Birds of air and sea, short-tailed shearwaters are “tubenoses,” related to albatrosses, petrels and fulmars. Their long narrow wings (they have a wingspread of about one metre) allow agile flight. Weighing just over half a kilogram, they are dark grey-brown with brown eyes, grey legs and webbed feet. Their oily feathers repel water so they don’t sink, but on land they are clumsy, barely able to walk and rely on strong winds to take off from the water.

Their nostrils are in long tubes on top of their bills, which funnel air into large olfactory chambers. Tubenoses have an acute sense of smell, allowing them to locate patches of krill or schools of small squid or fish. They feed on the surface, diving up to 20 metres to pursue prey underwater. Their keen vision helps locate prey. They drink salt water after glands in their heads remove much of the salt.

Photo by Brandon Qirqqut

Shearwaters live mostly at sea, returning to land only to breed. They use celestial navigation to return year after year to nest in the same burrow. The short-tailed shearwater breeds in South Australia and Tasmania, on islands and isolated sections of the coast. They mate for life and may live 20 to 30 years. A pair raises one chick per year, leaving the chick for a week at a time to go to sea to feed, returning to regurgitate a slurry that’s lower in mass than the prey itself, making it easier to carry on long flights. This oily (and smelly) substance is also regurgitated as a defense against nest predators.

During and after the breeding season, shearwaters head south into the Southern Ocean where they feed on an abundance of krill and small fish off Antarctica before setting off on their long northward migration. This takes them the length of the Pacific Ocean, past Japan and the Aleutians to the Bering Strait, the Chukchi Sea and beyond. They spend the northern summer in the North Pacific to the Beaufort Sea, then again migrate the length of the Pacific to arrive at their breeding grounds by September or October. Some travel more than 30,000 kilometres in their yearly migrations.

It’s not an easy life, and things are becoming more difficult. Biologists have recorded major increases in die-offs of seabirds, including murres, puffins and shearwaters, in the North Pacific and Bering Sea in recent summers. Since 2015, thousands of carcasses have been found washed up on Pacific shores, with the numbers of dead shearwaters increasing significantly between 2019 and 2024. Many birds die at sea and never reach the shore.

Necropsies revealed that most were emaciated when they died. This indicates extreme changes in their food supply, which most scientists attribute to warming oceans. A loss of sea ice means a loss of the algae that inhabits the underside of the ice, providing less food for plankton. Warmer water holds less dissolved oxygen, and the zooplankton at the base of the food chain either disappear or are less nutritious. Faithful to their migration routes, the birds arrive only to find no food.

Everywhere along their route, the hungry birds eat anything resembling food. The guts of many shearwaters are filled with pieces of plastic, some quite large. If this alone doesn’t kill them, they feed this to their young, diminishing the survival rate of the next generation.

The deviant course taken by some shearwaters in 2024—and a few other years—may have been caused by the failure of their natural food resources and by weather systems pushing them east along the Arctic coast. Then open water along the north Alaskan coast may have enticed them to continue flying east. Records from 1990, 1994 and 2020 lead some biologists to think that a new migration route (tentatively named the Canadian Arctic Flyway) could be developing due to the reduction of ice in the Northwest Passage. Some pelagic species may be finding their way to migratory routes down Hudson Bay or even into the North Atlantic via Baffin Bay and the Labrador Sea.

As of January 2025, Colin Fraser saw no short-tailed shearwaters circling overhead in the darkness along the Arctic coast. But millions of them gathered at breeding colonies in the southern hemisphere, incubating their solitary eggs in the darkness of the burrows. How will they fare in future years? Keep an eye on the sky and the sea and fight hard for reduction of ocean waste