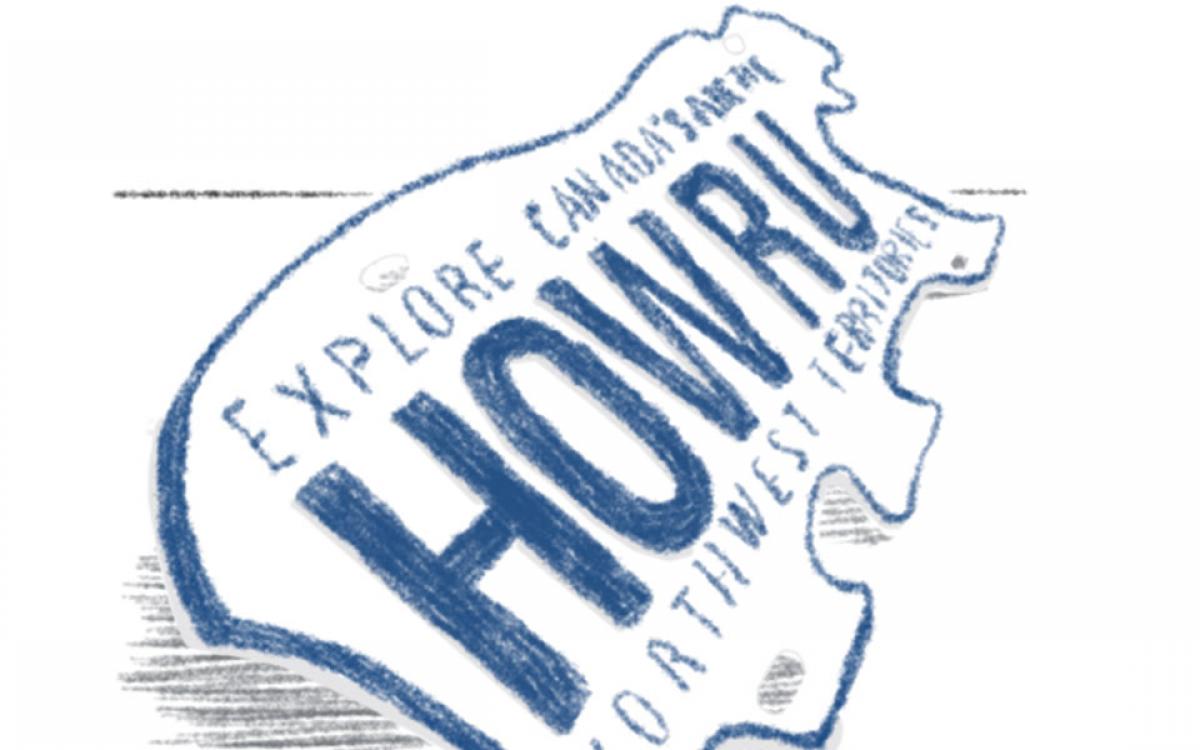

After five days of driving—and some periodic towing mixed in—my car made it to Southern Ontario. It had been there before. Six years ago, I drove it off a used car lot in North Toronto while the salesmen snickered about a faulty part or two they’d added to its rigging. But now, having arrived from Yellowknife, my Suzuki Vitara had a polar bear-shaped licence plate affixed to it.

This iconic design has been fastened to Northern vehicles—and later showcased on the walls of rustic cabins, dive bars and hipster coffee shops the world over—since 1970. The polar bear plate was introduced to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the establishment of the Northwest Territories.

In 1999, when Nunavut officially split from the Northwest Territories, neither jurisdiction was willing to give up their polar bear so both territories kept them. Since the Northwest Territories held the copyright, Nunavut drivers had a big ‘N’ stuck to the end of their licence numbers and NUNAVUT was spelled out in blue block letters across the white belly of the bear.

By 2011, Nunavut was ready for its own look. The government announced a design contest and a colourful night scene with a polar bear and inuksuk under sweeping Northern lights was selected. Nunavut also returned to the conventional rectangular shape.

Around this time, the NWT updated its plate. The design that spruces up the back of my car features the silhouette of a treeline and a bear across the bottom of the plate, waves of Northern lights brushing its edges. It’s quite busy when compared to the previous white-and-blue design. But it’s bear-shaped, so it still gets a lot of looks today.

Heading northbound on Highway 410 outside Toronto, a young man driving a sedan pulls up beside me and frantically gestures for me to roll down the windows. It’s rush hour. Socked in by cars on every side, we’re moving a steady five kilometres per hour.

“Did you just drive down from there?” he yells, as the heat and fumes outside flood into my car. At first, I figure he needs directions. (Or might he just be making the world’s most desperate attempt at a pick-up line?)

“From where?” I call back over the grumbling engines.

“The Northwest Territories!” he responds. I check my ego. “Did you just drive down?”

I just did, I tell him, before he jumps into a laundry list of questions. How long did the drive take? What is it like up North? How was the weather?

I answer them all as earnestly as I can, while still nudging forward, careful not to knock the bumper ahead of me. “Awesome,” he says. “Welcome to Ontario.” And then he buzzes away, closing the gap that had opened up in front of him while we were talking. The impatient commuter behind me lays on his horn.

Later that week, as I leave a general store in what Ontarians call ‘cottage country’ I find an older man taking a photo of my licence plate. “This yours?” he calls out as I approach. I nod and then he starts telling me how he lived in Nunavut—still the Northwest Territories, back then—for some 35 years. He’d owned a few polar bear plates himself. He was even there for Nunavut’s change to the rectangular plate. Today, it hangs proudly in his shed, displaying Nunavut’s independence. “I hadn’t seen this one yet,” he says.

I pull out of the lot and head home. I start to think, even 20 years from now, if I’m driving around in a car with a plain old, rectangular plate, the sight of the polar bear so far from the Northwest Territories will stop me in my tracks.

And I too will probably have the urge to ask the driver—whether we’re in gridlock on a busy thoroughfare or stopped in a parking lot—where they’re coming from and if they know Joe from Yellowknife.