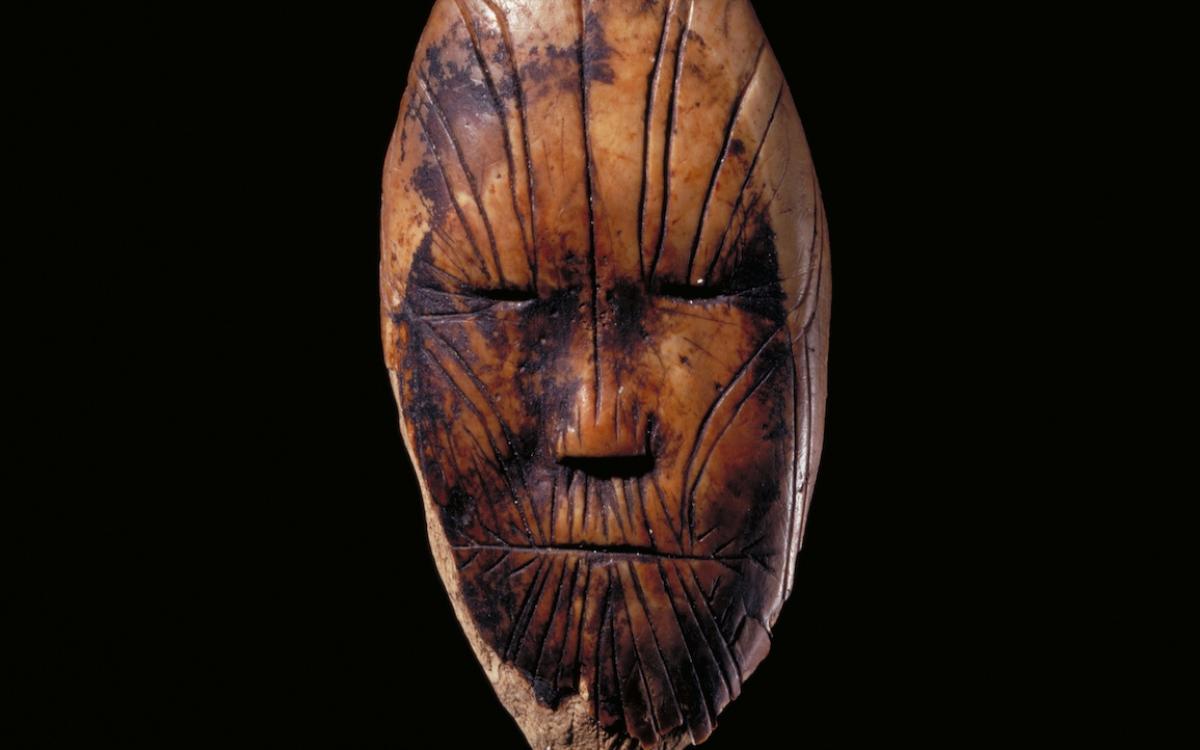

The face is only a few inches tall. The ivory is discoloured, golden-orange with dark stains filling its contours—a patina earned through millennia spent on Devon Island, Nunavut.

Deep lines carved into the ivory converge at two sunken eyes looming over an expressionless mouth. The longer you stare at this carving, called the First Face, the more lifelike it becomes. It’s as if the subject could awaken at any moment from a 4,000-year slumber.

The First Face is from a time when wooly mammoths weren’t yet extinct and the city of Babylon was brand new. Now it stares out at visitors to the Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec.

“I just look at her and think she was this peaceful-looking woman,” says Karen Ryan, northern curator for the national museum. “It’s pretty incredible.”

It’s the oldest known depiction of a human face in Canada. But northern art is far older. To fully appreciate the value of that antiquity means re-examining how art in the North has historically been interpreted.

When Arctic Indigenous groups began interacting more regularly with western traders in the 18th century, northern “art” became a commodity. But long before those days, carvings and other skillful creations were being crafted and artfully decorated. They were used as tools, toys, gifts, combs, and jewellery. Many of these pieces were created in a particular context, and sometimes by cultures that no longer exist and of which very little is known. Without that frame of reference, archeologists and art historians have—historically and problematically—defaulted to guesswork.

“Anything they don’t understand kind of becomes a mystical charm or amulet,” says Susan Irving, collections registrar for the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife. “Those are powerful words with huge meanings for certain people that we know nothing about. So I’m really careful about that sort of thing.”

Irving has a difficult time with what’s dubbed ‘art historical.’ It’s the way colonial powers have placed a value on old items from misunderstood cultures and commodified them as “art.”

British explorers took burial items from the tombs of ancient Egyptians because they were shiny, gold and exotic. Items sacred and religious were instead interpreted as beautiful, kept for aesthetic reasons, and ultimately wound up entering the commercial market. Their true value and meaning were ignored. History, uncompromisingly complex, is flattened, framed, and hung on a wall.

“If you are really being dishonest and just presenting this death mask as a beautiful thing to appreciate for its Euro-centric aesthetic reasons, then you’re simplifying the narrative,” says Irving. “You’re losing all that true richness.”

Thousands of years before those British explorers raided Egypt, when the last stone was being placed into the Great Pyramid of Giza, the oldest artwork in northern Canada was already ancient.

It’s a spear piece, crafted from caribou antler, carved with a series of rolling wave-like shapes. Carbon dating places the artifact’s age at 8,100 years—older than Ancient Greece by some five millennia. Empires around the world rose, fell, and rose again as the spear rested patiently in a mountain ice patch south of Gladstone Lakes (50 kilometres north of Haines Junction). There it remained, in the traditional territory of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, until it was rediscovered in the summer of 2000.

“We are still learning about why our ancestors may have carved a design onto this hunting tool, but knowing they did points to the sacred in everyday life activities, like hunting,” says Dän nätthe äda Kaaxnox (Chief Steve Smith).

The kwädāͅ y kwädǟn tool (meaning belonging to “our ancestors or long ago peoples” in Southern Tutchone) is not just a dusty artifact to the Champagne and Aishihik. It’s a piece of living heritage passed down through the eons.

Ten thousand years ago, or thereabouts, an ancestor of the Mountain Dene was walking through the Mackenzie Mountains with a prized stone blade on their person. Now, it lives tucked away inside the Prince of Wales’ archives. The grey-blue chert stone, about 15 centimetres in length, has evenly flaked ridges running like lake ripples down its body. The skill involved in making such a precise piece is “stunning” says Irving.

“These things would be highly prized,” she says. “To have found one, it just represents a huge loss for someone who dropped it out of their pocket. ‘Ah shit, my knife, I left it up there.’”

She’s guessing at what happened, of course. The “oblique, transverse flaking” stone tool was found in an ice patch and that much is certain. The rest is an educated guess. It looks like a knife blade. The skill involved in its creation appears to be out of the ordinary. There’s no carbon to date the stone, but similar pieces found in North American sites to the south have been dated to 10,000 years old. Is it that old? No one can say. Is it art? Well, the knowledge of the material, the practice involved to craft something of this sort, it’s more than just tool-making.

But is it art? Irving can’t say. She only knows what happens when she looks at it.

“Immediately, it’s a feeling here,” she says, holding her hand tightly to her chest. “And I want to cry. I immediately see the hand that made it and the hand that held it. I have an emotional reaction to that sort of thing.”

It’s possible the oldest art in the North isn’t anything tangible at all. Not an object buried in the past but something alive, worth preserving. A tradition passed down through generations—the design of a tattoo, the movement of a dance, the rhythm of a language offering continuity through time.

“But we like to have a visual thing,” Irving responds. It’s easy to see why. Looking at faces carved by human hands bridges an unfathomable distance.

“Is that somebody’s family or friends?” asks Ryan. “You feel like you almost know them.”

Almost.